SPACE November 2025 (No. 696)

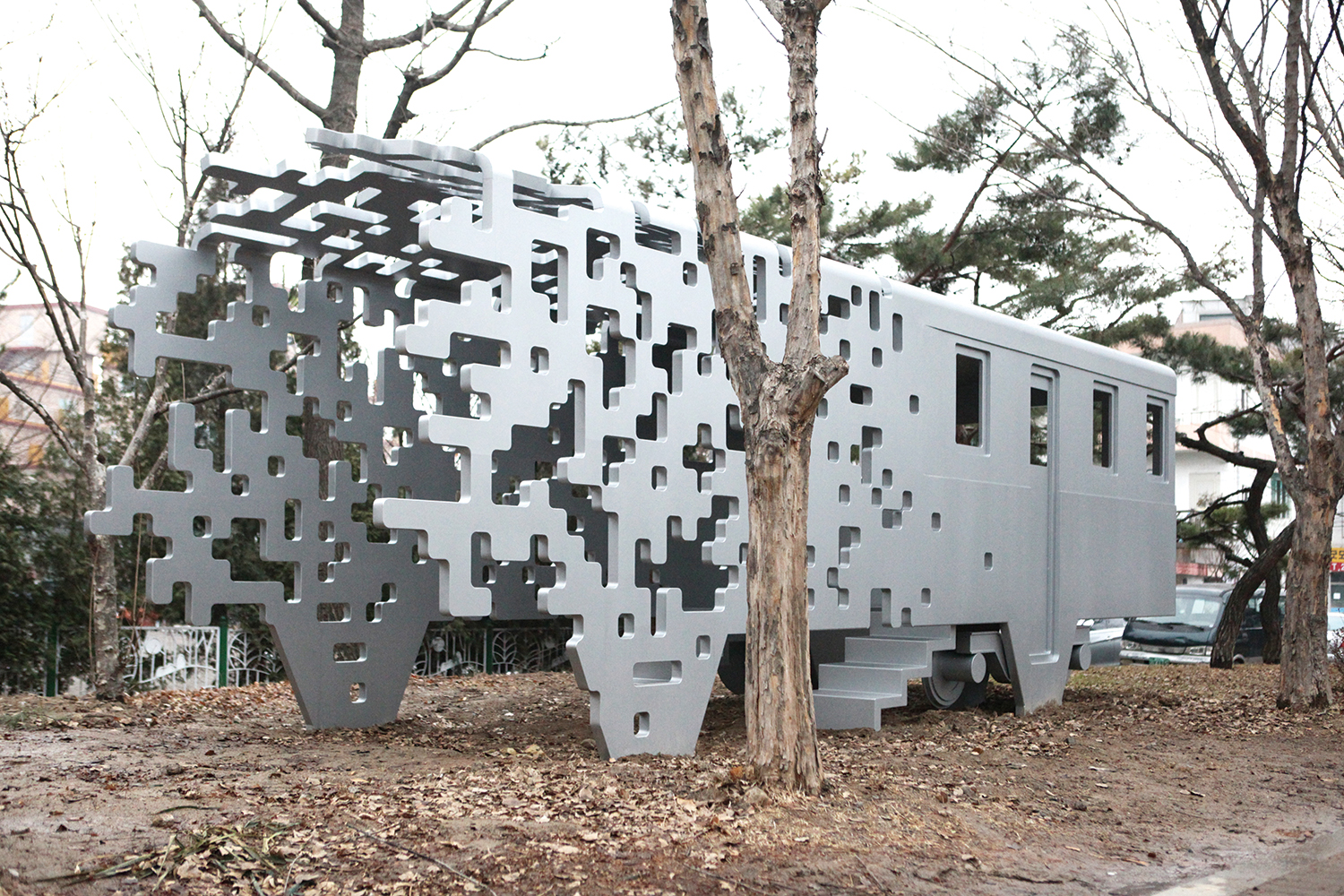

SoftShelf (In collaboration with Brian Brush, 2008) ©Lee Hokyung

In architectural education and practice in Korea, reading the context of a site and responding to it is regarded as an absolute. Any attempt to express formal intentions too overtly invites harsh criticism. Efficiency and economy firmly support the foundation, while layers of external constraints – historical, cultural, social conditions, as well as regulations and structural requirements – accumulate above. Only the ‘mass’ refined through a faithful reflection on these aspects throughout the design process is acknowledged as architecturally legitimate. This attitude is valid to some extent, as it understands architecture as a social product, however it simultaneously restricts the potential for new experimentation. That said, not all architecture must operate in this way. Architecture can also emerge autonomously, governed by its own internal logic and order rather than subordinated to external conditions. This is not a denial of context but an attempt to reconsider the generative principles of architecture beyond the given framework. Such an approach may at times appear unfamiliar or inefficient, yet it is precisely within these uneven attempts that new possibilities arise. Architecture that departs from familiar conventions is often regarded as strange, but the solidity that gives form to this strangeness enhances the completeness of the experiment and deepens the nuance of a work of architecture.

A series of works emerging from this line of inquiry can be categorised into five design approaches: computational thinking, fabrication techniques, process, materiality, and the exploration of tradition. Each addresses different layers, yet they ultimately meet as a single system of thought. Together, they expand architecture from a response to external demands into an act of reorganising the world through its own internal structure.

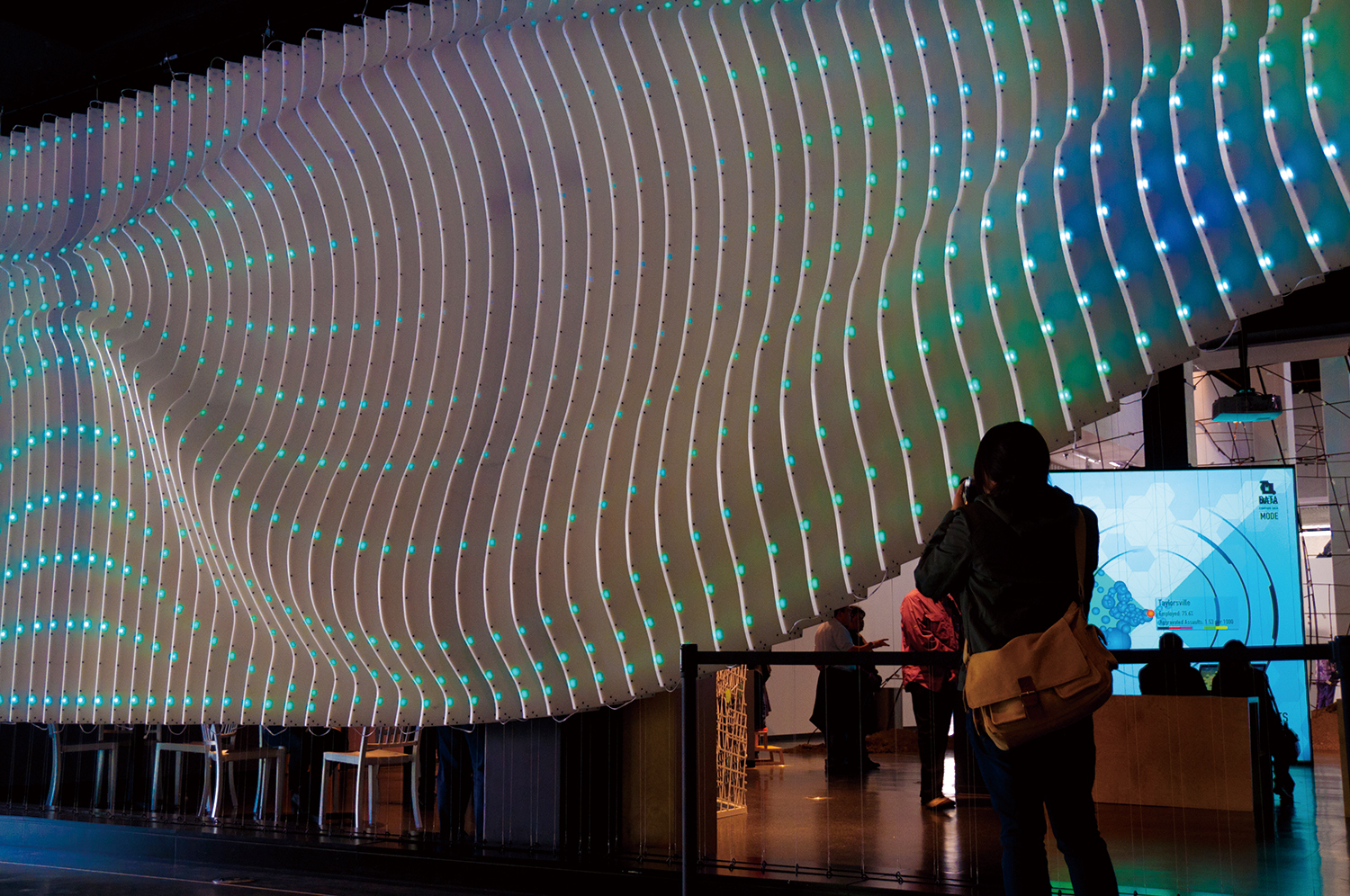

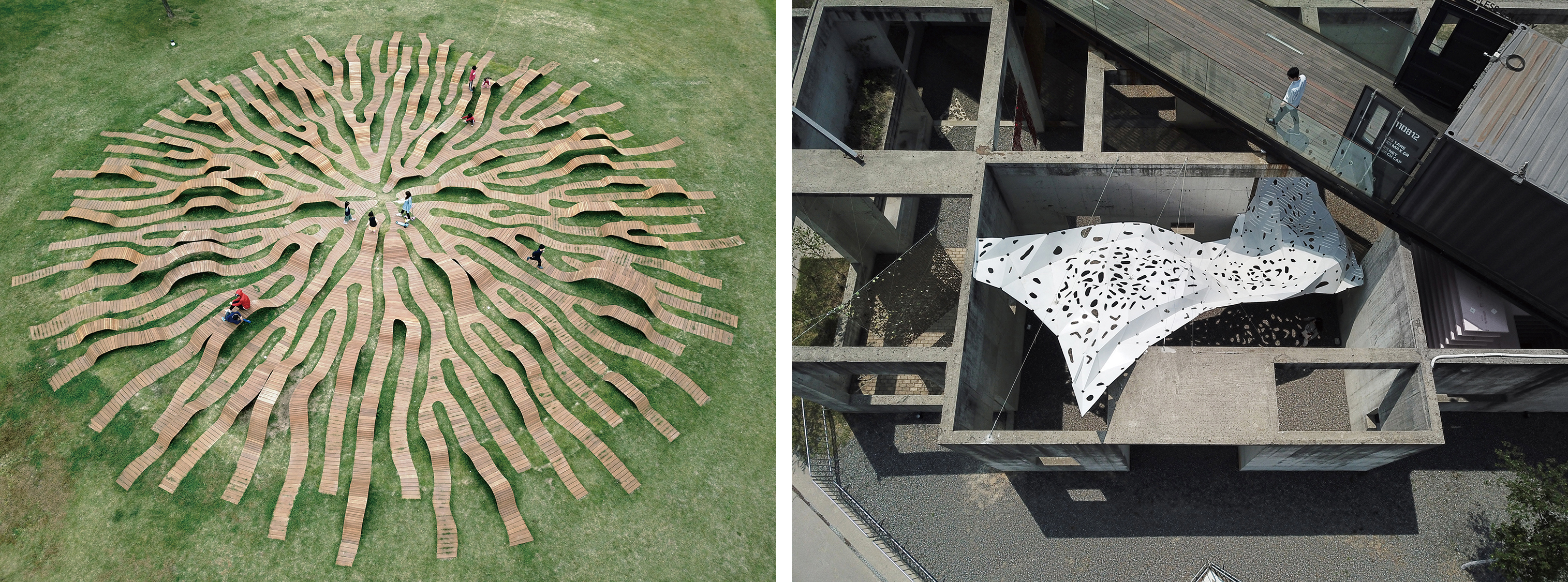

Dynamic Performance of Nature (In collaboration with Brian Brush, 2011)

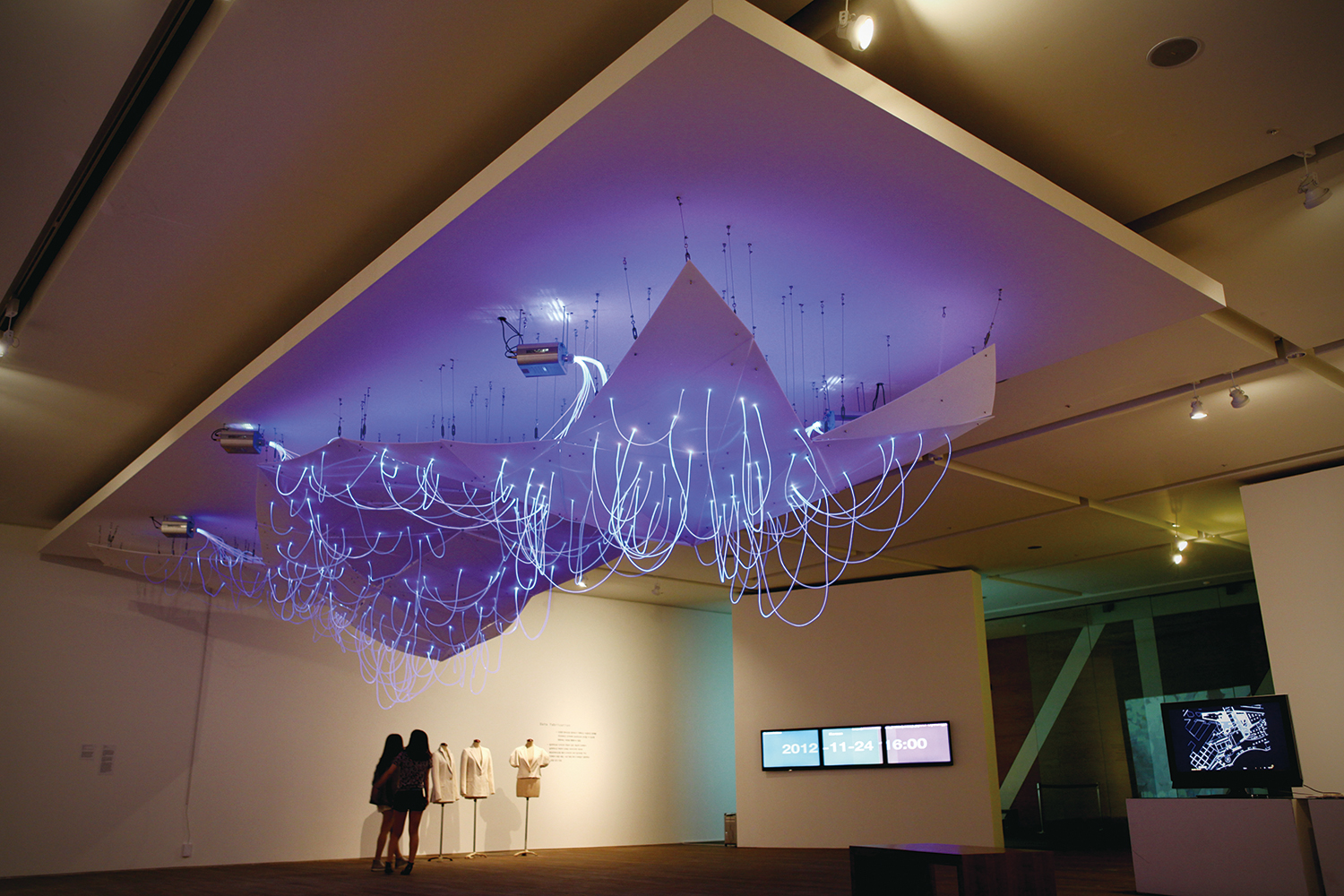

SEAT (In collaboration with Brian Brush, 2012)

Computational Thinking

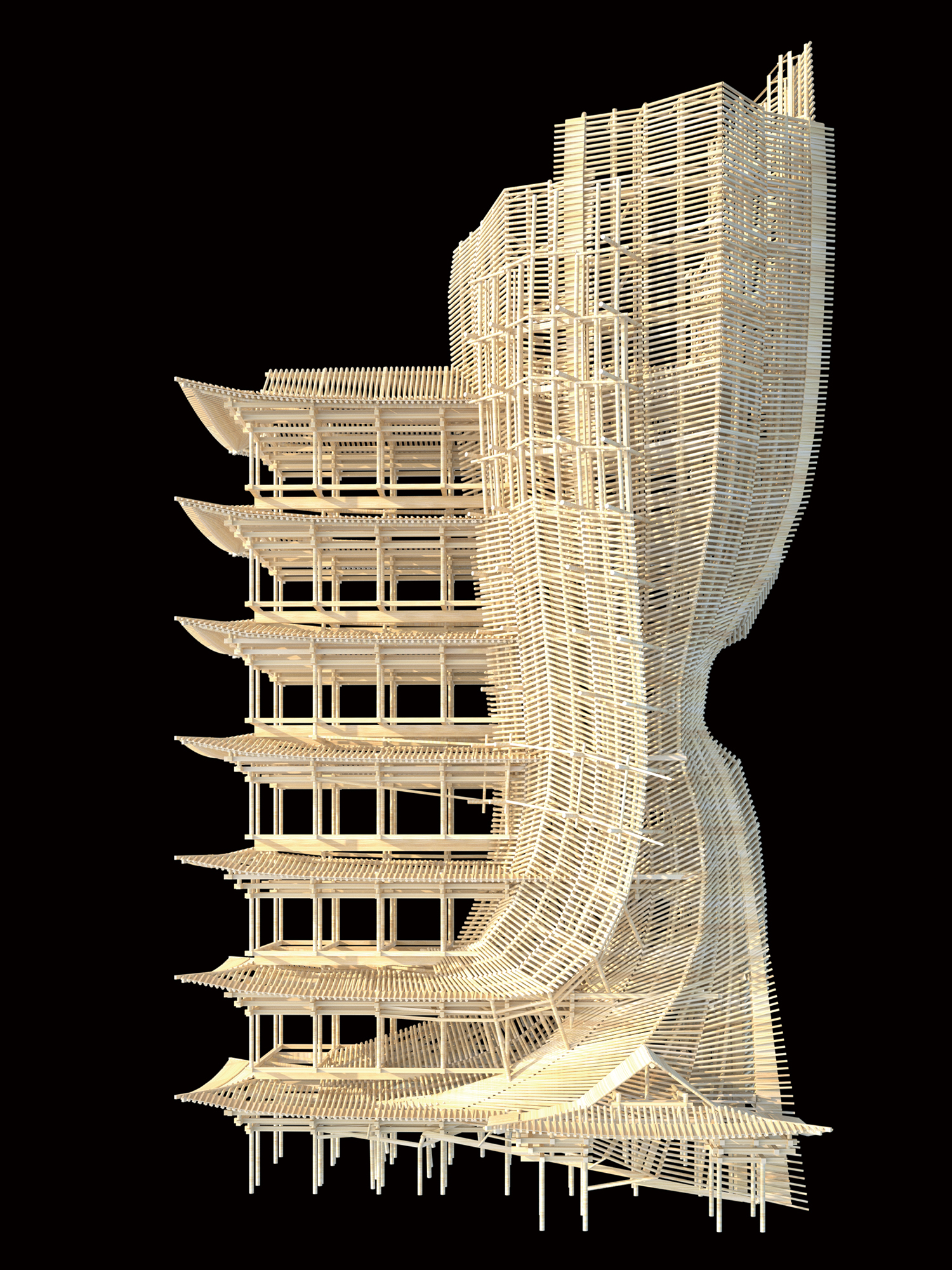

Computational thinking is an attitude that places the construction of logical systems, including mathematical operations, at the centre of the design process. Rather than relying on external contexts or conditions, it values the generation of form through the internal logic of rules and relationships. Here, ‘computation’ is not merely calculation but a mode of thought in which multiple variables interact to produce a certain order. This operation can occur through various tools—computers, calculators, notebooks, or even within one’s mind. Form is not a predetermined outcome but something that emerges within the iterative process of conditions and rules at work. The architect’s role is not to complete drawings, but to set the operative parameters, observe the process, and make adjustments along the way. For example, Topology: Hanok (2025) determines both the form and fabrication method simultaneously under optimised conditions among changing prompts, endlessly generated sectional sequences, selected combined masses, and the processing techniques of an industrial robotic arm. This shift in thinking views architecture not as a finished product but as a continuously evolving and expanding system. Such an approach goes beyond the auxiliary use of digital tools such as parametric design or BIM, evolving instead into a methodology that structures the very thought process of design.

In the early stages of this work, the possibilities were explored through real-time data visualisation and algorithmic modeling techniques. Now, however, the focus lies not only on the functional aspect of tools but on the flow of thought that occurs within them. Computational thinking is not a technique of calculation but a framework of reasoning that defines relationships, adjusts variables, and generates new orders through rules. Within this process, architecture is no longer understood as a fixed outcome, but as an open system in which internal orders manifest as external forms. Recently, the emergence of AI has further expanded this trajectory.

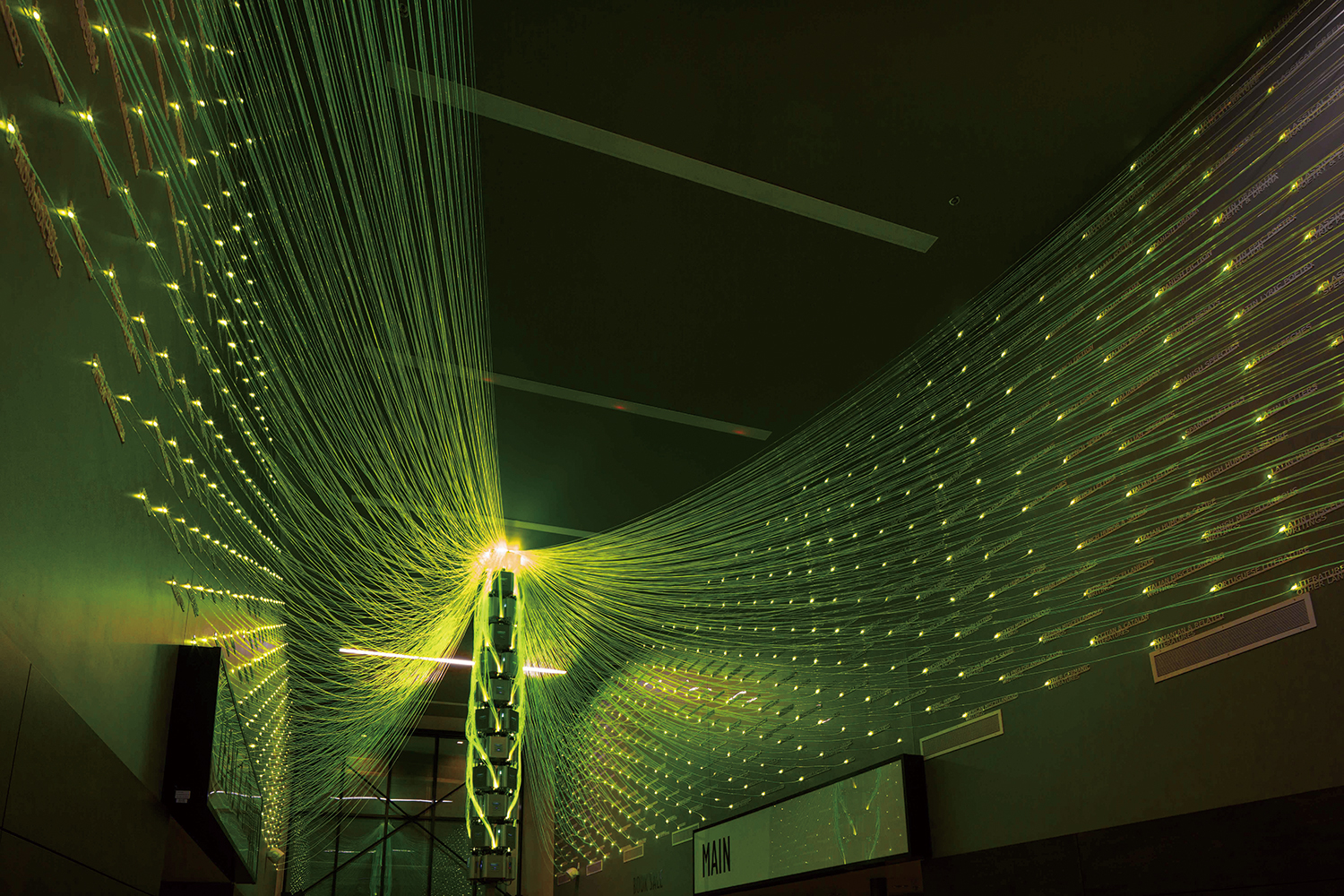

Filament Mind (In collaboration with Brian Brush, 2013) ©David Agnello

Mood Map (In collaboration with Brian Brush, 2013)

Vernacular Versatility (2014)

Advanced Fabrication Techniques

The outcomes produced through computational thinking often, intentionally or otherwise, take on complex and exaggerated forms. To materialise these forms into physical space, research on fabrication methods must necessarily be involved. A fabrication technique is not merely a tool for realising form, but a process in which thought is translated into material. Alongside computational thinking, it functions as a major axis in most projects. Tools such as industrial robotic arms, CNC milling, and 3D printing serve not simply as instruments of efficiency, but as experimental devices that visualise and verify the process of thought. Fabrication is not a post-design phase but an integral part of the design process itself, progressing in parallel from the conceptual stage to construct new forms of order in the real world. This approach does not interpret advanced technology as a means of automation or precision alone. Rather, it proposes a new sensory system in which human hands, thought, and technical instruments operate together. The robot does not replace human labour but functions as a tool that expands human thought and extends the boundaries of experimentation. The numerous errors and deviations that occur in fabrication are accepted not as flaws but as parts of the experiment, gradually evolving toward the goal of controlling such variables. Technology, rather than producing completed architecture, sustains a state of incompletion that allows continuous transformation. Advanced fabrication techniques are not merely the capability to produce precise results, but the establishment of an open system in which thought and matter continuously renew each other.

Dispersion (2015)

Conflux (2017)

Process-Oriented Approach

In projects dealing with new concepts or technologies, designing the design process itself becomes the most crucial task. Since such works often rely on methods that did not previously exist, the essence of design lies not in what to make but in how thought unfolds and how physical transformation occurs. The notion of mealworms consuming plastic, widely circulated in online articles, was first explored in the miniature project Worm Skyscraper (2020) which showed worms gnawing on plastic. This approach later evolved into Decomposition Farm_Stairway (2022, covered in SPACE No. 664), realised as part of an architectural structure through the combination of an industrial robotic arm and heated-line processing, and further expanded in Strata of Decomposition (2025), which scaled up and adapted the method to actively address architectural waste. In this way, process is a means of shaping a structure of thought, where technology, materials, and space mutually influence each other to generate new relationships. This approach ultimately produces a ‘narrative’ as a continuous flow. The narrative serves both as the starting point of the design and as a connecting mechanism for the process, aligning logical steps and a sensory flow. Thus, the architectural process can be read as a story, in which each stage functions not as cause and effect but as an accumulation of meaning. This approach is closely connected to a mode of thinking often described as speculation. Speculation here is a process of verifying and expanding thought through actual experimentation. The designer deliberately sets unpredictable conditions and observes what emerges within them. The flow of these processes itself becomes the driving force for generating new ideas. For example, accepting algorithmically generated forms or material transformations as they are, and discovering order within them, can be seen as a speculative practice. Such an attitude does not aim for a perfect result but rather embraces unpredictability as an essential part of experimentation. It is in that uncertain moment – when thought is translated into matter – that creative potential arises. Architecture, in this sense, is no longer a means of realising predetermined forms, but an open structure in which thinking and experimentation evolve together.

Wing Tower (2017)

Myeonmok Fire Station (2017) ©Kyungsub Shin

Sustainable Materiality

Concrete and steel – the materials that embody the modern value of efficiency – have defined architecture for over a century (or roughly seventy years in the Korean context). Yet the values we have long taken for granted can change abruptly, especially in matters concerning the environment. Today, sustainability in architecture is no longer limited to questions of energy efficiency or recycling. It involves redesigning the life cycle of materials and embracing their transformation and decay as integral parts of time itself. Biodegradable materials such as mycelium, which can deform and decompose on their own, bring the uncontrollable variables of nature into the realm of design. Working with such materials is less about shaping a complete form and more about orchestrating a living system. Architecture thus ceases to be a fixed object but an entity which grows, withers, and continuously changes over time. Material is no longer the means to construct form, but an active agent that drives the process of construction itself.

This approach also represents a strategic response for those entering the technological race as latecomers. Even with the active adoption of computation and advanced technologies, it is difficult to compete with global pioneers merely through precision or speed. Therefore, by focusing on eco-friendly materials, one can compensate for technological limitations, enrich the process, and deepen the narrative of architecture. Above all, this is a fundamental approach to an issue shared by all humanity – environmental and ecological sustainability – an approach that no one can dispute.

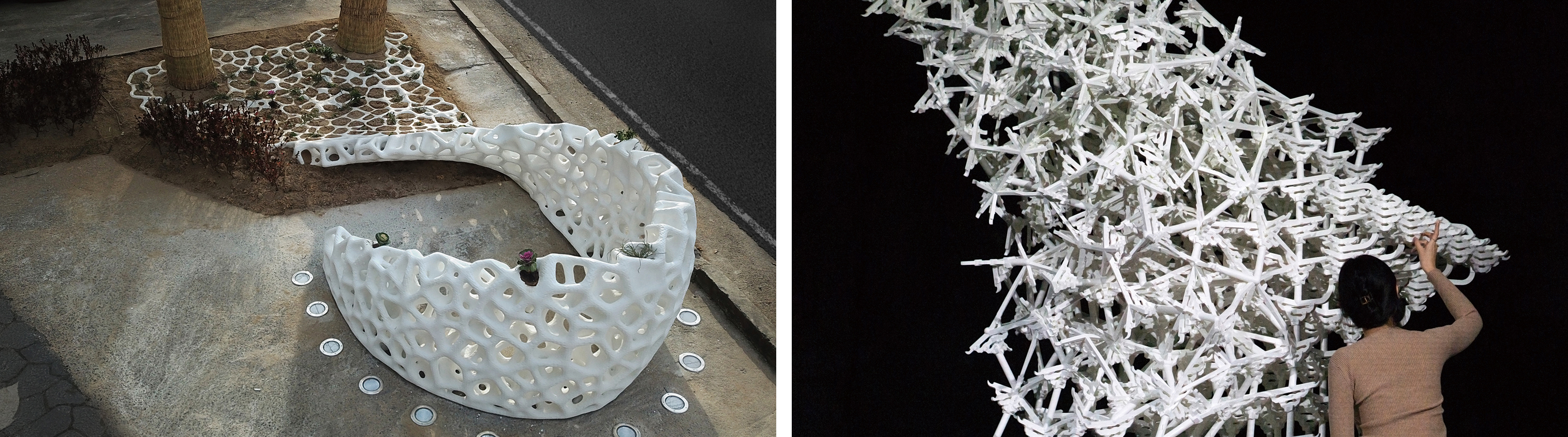

(left) Root Bench (2018), (right) The Wind Shape (2019)

(left) Wave Pavilion (2020), (right) Versatile Bracketry (2021)

(left) Wave Pavilion (2020), (right) Versatile Bracketry (2021)

Reinterpreting Tradition

Just as sustainable materials offer one strategic axis, our tradition constitutes another—one that can be intertwined with computation. It is a topic that never appears within the technology-driven architectural research of the West, yet it is grounded in the logic of our own cultural thinking. In a field where Western technology advances at an overwhelming speed, studying Korean tradition paradoxically grants the freedom to control that speed. Because this is a field unclaimed by competitive research, one can determine the pace of experimentation on one’s own terms. Exploring the inner order of architecture ultimately leads to a structural way of thinking rooted in tradition. Tradition is not a matter of restoring past forms or aesthetics, but of reconstructing the principles of relationships embedded within them in the language of the present. The joining systems of timber structures, the proportional logic of the hanok, and the physicality of materials already contain sophisticated mathematical orders and algorithmic thinking. To reinterpret these through contemporary technology and computational thinking is to transform tradition from a memory of the past into an experiment for the future.

In this field, working with tradition is closer to transformation than to restoration. Digital fabrication techniques allow the structural wisdom of the past to be re-examined within new materials and contexts. Tradition is not a fixed identity but an open system that continuously renews itself through the flow of time and technology. At the point where past and present, matter and data, the artisan’s touch and algorithmic computation collide and overlap, a new order emerges. At this moment, tradition no longer functions as a reproduction of the past but as a variation in time, allowing architecture to reinterpret the sensibilities of the present through its rhythm. In this moment, tradition no longer functions as a reproduction of the past, but as a modulation of time through which architecture reinterprets the sensibility of its age.

(left) Flower Ring (2022), (right) Decomposition Farm_Stairway (2022)

Machum House (2023)

Moss Columns (2024)