SPACE November 2025 (No. 696)

The 5th Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism is currently taking place in sites across central Seoul, including Songhyeon Green Plaza, Gwanghwamun Square, and the Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture. Opening on the 26th of September, this year’s Biennale carries the theme ‘Radically More Human’. Thomas Heatherwick (director, Heatherwick Studio), general director of the Biennale, focuses on the architectural façade as a key strategy in creating cities that feel more human. SPACE examines how this design and curatorial idea is being realised in the planning and execution of the exhibitions, while also reflecting on the challenges and limitations revealed in an event that places ‘popularity’ as its foremost concern.

The Walls of Public Life visible beyond the Humanise Wall. ©Bang Yukyung

Now in its fifth edition, the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism (hereinafter the Seoul Biennale) drew major attention from the outset when Thomas Heatherwick, one of Britain’s leading architects and designers, was appointed as general director. The announcement was met with both anticipation and concern; anticipation at how a creator known for his inventive and engaging formal language might infuse Seoul with a new energy, and concern that the event could devolve into a one-off spectacle built on the fame of a star architect. In fact, Heatherwick was commissioned as general director in June 2024, shortly after winning International Design Competition for the Nodeul Global Art Island. Setting aside the controversy surrounding that competition within the architectural community (covered in SPACE Nos. 677, 680, 684), questions still lingered over whether he could, within such a short period, fully grasp and interpret the urban and architectural context of Seoul in order to curate an exhibition on this scale.

The theme of this year’s Seoul Biennale, ‘Radically More Human’, is also a question that Thomas Heatherwick has long pursued. In essence, it suggests that architecture which feels attractive to people is, by nature, human-centred architecture. In the exhibition preface, Heatherwick stated that through the Biennale he sought to ‘explore how the façades of buildings affect society as a whole, and how deeply architecture is connected to our emotions.’ This perspective is also fully reflected in his book HUMANISE (2023), published in Korea in 2024. The book opens with an image of Heatherwick holding a volume that features a photograph of Antoni Gaudi’s Casa Milà, highlighting his fascination with its sculptural and crafted exterior—a striking contrast to the monotony of flat, modernist buildings. He writes that façades imbued with craftsmanship ‘have provided immeasurable joy to hundreds of millions of passersby.’ If his vision of humanistic architecture unfolds through the medium of ‘the building’s surface that moves human emotion’, then the key to viewing this Biennale lies in observing how that message takes form and expression within the context of Seoul—and how it engages the public across different media and modes of experience.

General director Thomas Heatherwick presenting at the opening ceremony. Image courtesy of Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism

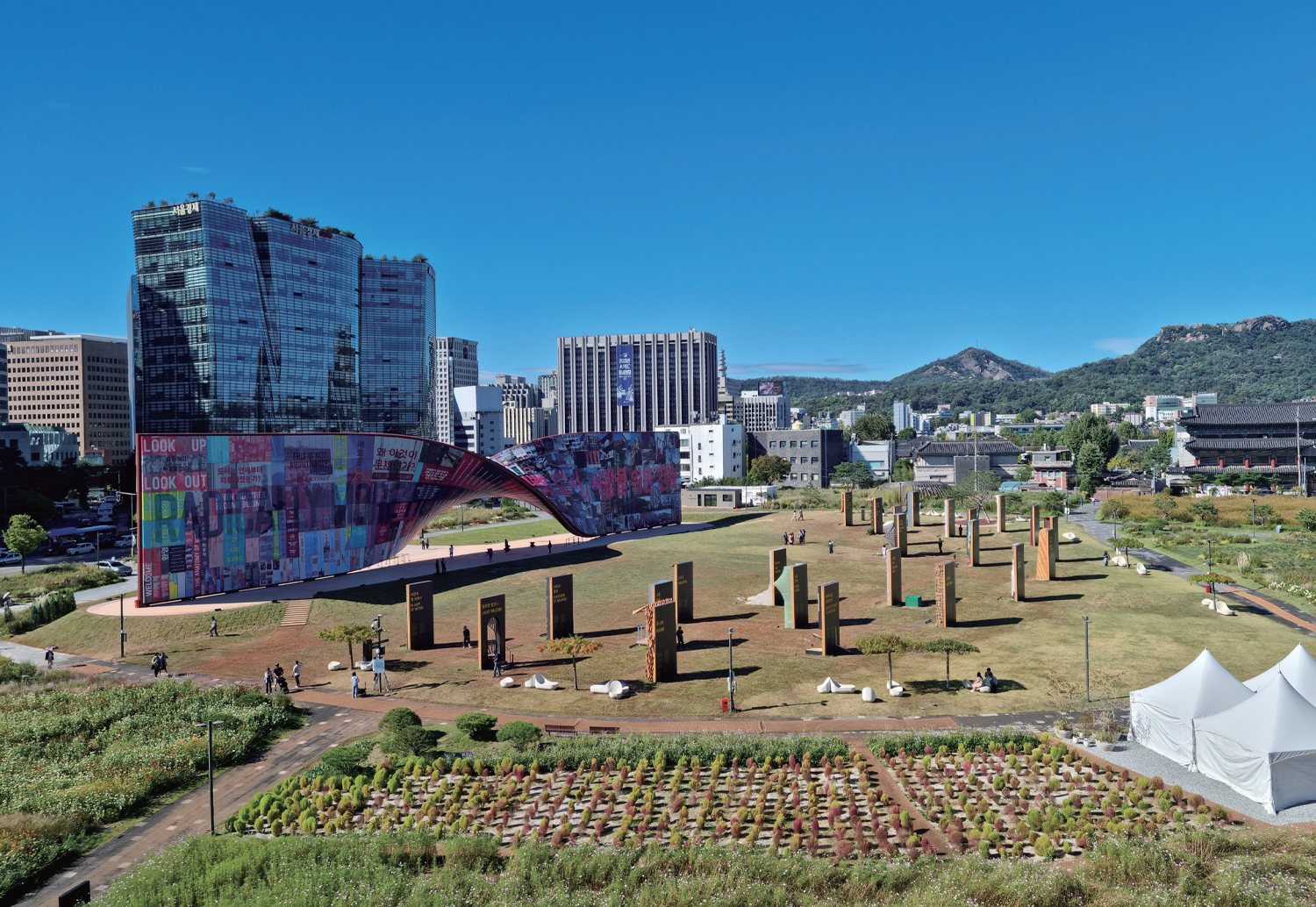

The exhibition is composed of four main sections: the Thematic Exhibition, the Cities Exhibition, the Seoul Exhibition, and the Global Studios. Leading the programme, Thomas Heatherwick curated the Thematic Exhibition, which mainly unfolds across two parts: Humanise Wall and Walls of Public Life at Songhyeon Green Plaza (hereinafter Songhyeon Plaza). The Humanise Wall, serving as the centrepiece of this Biennale, takes the form of a ‘wall’, a symbolic architectural element that defines the façade of buildings. Measuring 90m in length and 16m in height, the steel-framed structure is clad with 1,428 steel panels layered like scales. The central portion twists like a ribbon, creating a circular opening that connects the inner and outer spaces of Songhyeon Plaza, where the exhibition is held. Heatherwick envisioned this wall – imbued with the message of human-centred urban architecture – as a communicative threshold that sparks dialogue and catalyses social change. Beyond the Humanise Wall, numerous walls rise across the lawn inside the park. This section, titled Walls of Public Life, features a series of creative façade mock-ups, each measuring 2.4m-wide and 4.8m-high, differentiated by materials, textures, and patterns. The 24 participating teams include professionals from a range of disciplines—writers, chefs, jewellery designers, fashion designers, and architects from both Korea and abroad. Responding to the general director’s request to ‘create façades that feel intriguing and engaging’, the participants employed a diverse palette of materials and combinations, including water, wood, brick, clay, mold, fabric, concrete, plastic, and steel.

Overall view of the Songhyeon Green Plaza where the Thematic Exhibition is being held. ©Bang Yukyung

The same sense of disconnect between form and content was evident in the Walls of Public Life section. Visitors stopped to take photos in front of the walls or to read the descriptions written on their reverse, but such engagement was fleeting. Standing in the middle of a vast open field, the walls functioned less as spatial installations to be experienced and more as flat images—largely consumed as backdrops for social media snapshots. One cannot help but wonder why, in such an expansive setting, the works were constrained by the fixed format of a ‘single-surfaced wall’ of a prescribed size. From the scale of the plaza, the walls appear small, yet in reality they are not; their ambiguous spacing prevents each element from being appreciated as an independent work. Despite the presence of 24 walls, there seems to be little relational consideration for how they might interact or engage in a creative dialogue with one another. The reverse sides of the walls, meanwhile, were treated simply as plain panels listing artwork information and design intent.

Exhibition view of Walls of Public Life. ©Bang Yukyung

In the case of the Cities Exhibition, brief texts, photographs, and drawings related to each building were arranged along the floor in a plinth-like format, yet the content leaned towards general overviews rather than detailed explanations or careful analyses aligned with the exhibition’s theme. The Seoul Exhibition, which was organised based on a project list preselected by the Seoul Metropolitan Government, largely consisted of unbuilt works; as a result, it relied on renderings and aerial perspectives, making it difficult for viewers to experience the architectural reality of each project. In this way, both exhibitions compressed the discussion of building façades into a series of images printed on curtains, reducing what could have been meaningful inquiries into the influence or implications of individual buildings within urban space to momentary spatial impressions. Despite being curated under a shared theme, they fell short of revealing, through deeper analysis, any substantive connection or expansion between the Seoul projects and those from abroad—an omission that feels particularly regrettable when recalling the research-based exhibitions of previous Biennales.

Exhibition view of the Cities Exhibition at the Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture. ©Bang Yukyung

This critical awareness was also recognised from within. Maya West, a Korean-born artist who was invited to participate in Creative Communities Project, part of the Thematic Exhibition, and presented ‘Living Together in the World’ with Melody Song, remarked that ‘coming to a divided nation and blithely building a huge wall shows a profound lack of judgment and taste’, criticising Thomas Heatherwick for simply imposing his own narrative without any meaningful engagement with Korea or Seoul.▼1 Similarly, Elliot Woods, a member of the Seoul-based art and technology duo Kimchi and Chips, who participated in the previous Seoul Biennale and presented the media wall Reworld at Songhyeon Plaza, pointed out that considering the site’s history – a space closed to the public for 110 years under Japanese and later U.S. control before finally reopening in 2022 – the choice of a ‘wall’ as a central motif was profoundly inappropriate.▼2

Exhibition view of the Seoul Exhibition. Image courtesy of Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism

Meanwhile, the Global Studios programme, which collects a diverse range of voices on cities and architecture and visualises them through AI analysis, though still in its early stages, represents an attempt to expand civic engagement online. It offers an opportunity to reconsider how ordinary people perceive and experience everyday urban spaces, such as apartment complexes that architects too readily dismiss as monotonous. The interactive media wall showcasing this project was placed quietly in a corner of the Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture, making its presence appear rather subdued. Still, it raises the question of whether the Seoul Biennale should define its future direction on the foundation of such experimentation and discovery, using rapidly evolving technologies to gather public opinions and archive discussions about the city.

_

1 Christina Yao, ‘Seoul creatives brand Heatherwick’s Humanise Wall “a profound lack of judgment”’, Dezeen 3 Oct. 2025, https://www.dezeen.com/2025/10/03/heatherwick-humanise-wall-seoul-biennale/, accessed 17 Oct. 2025.

2 Ibid.